Force:

Force is a push or pull by which the state of the object changes or tends to change.

Types of forces:

There are two types of forces-

1.) Contact Force

2.) Non-Contact Force

1.) Contact force:

When there is physical contact between the two objects by push or pull then it is known as contact force.

For Example:

i.) When a coiled spring is stretched (pulled), the two ends of the spring must be in actual contact with the person's hands.

ii.) Kicking a football, and pulling a cart are also contact forces.

Types of Contact Force:

I.) Applied Force

II.) Frictional Force

III.) Normal Force

IV.) Tension Force

V.) Air Resistance (Drag Force)

VI.) Elastic or Restoring force

I.) Applied Force:

When a force is exerted by a person or an object to another person or object then this force is known as applied force.

$F=ma$

Example: Pushing a shopping cart, pulling a door open.

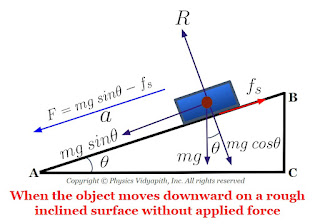

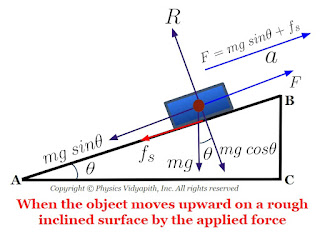

II.) Frictional Force:

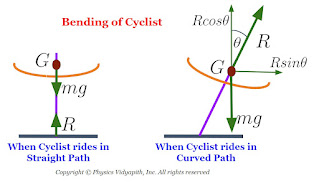

When two surfaces are in motion relative to each other and in contact then a force acting in the opposite direction of the motion of one surface over the other is called the force of friction. The frictional force is also called the force of friction or simply friction.

$F=\mu R$

A smooth surface exerts a lesser force of friction than a rough surface. The rolling frictional froce is always less than the sliding frictional force.

Types of Friction Force:

i.) Static Friction:

When the frictional force is applied on the object due state of the rest of the object then frictional force is known as static friction.

ii.) Kinetic Friction:

When the frictional force is applied to the object due motion of the object then frictional force is known as dynamic friction.

iii.) Limiting Friction:

The maximum value of static frictional force is known as limiting friction.

Example: Rubbing hands together, a car’s brakes stopping a vehicle

III.) Normal Reaction Force:

When an object is placed on a surface (or another object), the object exerts a force on the surface (or another object) vertically downwards. However, the object does not move in the direction of the force. This is because the surface (or another object) exerts an equal and opposite force on the object vertically upwards. then this force is called normal reaction force.

$Normal \: reaction \: force (N) = Weight \: of \: the \: object (mg) $

Example: A book resting on a table, a person standing on the ground.

IV.) Tension force:

The force on the string, rope, or cable due to pulled tight is known as Tension.

Force is transmitted through a s when pulled tight.

Example: A person pulling a rope in a tug-of-war, a hanging lightbulb.

V.) Air Resistance (Drag Force):

It is a type of friction force that acts against objects moving through the air.

Example: A parachute slowing down a skydiver, wind resistance on a car.

VI.) Spring Force (Elastic Force Or Restoring force):

A force that always acts in the opposite direction of the object's displacement is known as elastic or restoring force.

Example: A compressed spring in a toy, a rubber band being stretched.

2. Non-Contact Forces (Act at a distance)

I.) Gravitational Force (F)

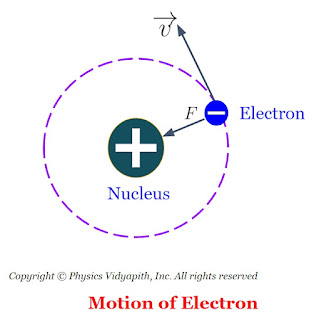

The force of attraction between two heavy objects is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

$F=G \frac{m_{1}m_{2}}{r^{2}}$

This force is most effective between very heavy objects like satellites, Planets Su,n and Stars.

Example: Objects falling to the ground, Earth’s gravity keeping the Moon in orbit.

II.) Electromagnetic Force:

When electric force and magnetic force are applied perpendicular to each other on charged particles then a force acts perpendicular to both this force is known as electromagnetic force.

The force between charged objects include both electric force and magnetic forces.

Example: Lightning (electric force), magnets attracting iron nails.

i.) Magnetic Force:

The force between magnetic materials, either attracting or repelling is known as magnetic force. The magnitude of magnetic force due to moving charge is described by Lorentz's law ($F=qvB sin \theta$)and direction is described by Fleming's left-hand rule. Similarly, the magnetic force due to the conductor is described by the formula $F=iBl sin\theta$ that is deduced by Lorentz's law, and the direction of force in a conductor is also described by Fleming's left-hand rule.

Example: A compass needle pointing north, fridge magnets sticking to a fridge.

ii.) Electric Force:

The attraction and repulsion force between the charges is known as the electric force. The magnitude of this force is described by Coulomb's law and the direction is described by the vector form of Coulomb's Law.

$F=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{\circ} K} \frac{q_{1}q_{2}}{r^{2}}$

IV.) Nuclear Forces:

The force between the nucleons (i.e. proton and neutron) is known as nuclear force. Nuclear forces are two types.

i.) Strong Nuclear Force:

It is the very strongest and short-distance force that holds protons and neutrons together in an atomic nucleus.

ii.) Weak Nuclear Force:

When the nucleus is involved in radioactive $\beta$ decay then the force between the particles is known as weak nuclear force. The force is involved in the reaction of nuclear fission and fusion.

Example: The energy released in nuclear reactions, like in the Sun or nuclear power plants.

2.) Non-Contact Force

ii.) Kicking a football, and pulling a cart are also contact forces.

II.) Frictional Force

III.) Normal Force

IV.) Tension Force

V.) Air Resistance (Drag Force)

VI.) Elastic or Restoring force

%20and%20linear%20velocity%20(%E2%8D%B5).jpg)