Equation of eigen value of the momentum of a particle in one dimension box:

The eigen value of the momentum $P_{n}$ of a particle in one dimension box moving along the x-axis is given by

$P^{2}_{n} = 2 m E_{n}$

$P^{2}_{n} = 2 m \frac{n^{2} \pi^{2} \hbar^{2}}{2 m L^{2}} \qquad \left( \because E_{n}= \frac{n^{2} \pi^{2} \hbar^{2}}{2 m L^{2}} \right)$

$P^{2}_{n} = \frac{n^{2} \pi^{2} \hbar^{2}}{L^{2}}$

$P_{n} = \pm \frac{n \pi \hbar}{L}$

$P_{n} = \pm \frac{n h}{2L} \qquad \left( \hbar = \frac{h}{2 \pi} \right)$

The $\pm$ sign indicates that the particle is moving back and forth in the infinite potential box.

The above equation shows that eigen value of the momentum of the particle is discrete and the difference between the momentum corresponding to two consecutive energy levels is always constant and equal to $\frac{h}{2L}$

Electric field intensity due to uniformly charged solid sphere (Conducting and Non-conducting)

A.) Electric field intensity at different points in the field due to the uniformly charged solid conducting sphere:

Let us consider, A solid conducting sphere that has a radius $R$ and charge $+q$ is distributed on the surface of the sphere in a uniform manner. Now find the electric field intensity at different points due to the solid-charged conducting sphere. These different points are:

1.) Electric field intensity outside the solid conducting sphere

2.) Electric field intensity on the surface of the solid conducting sphere

3.) Electric field intensity inside the solid conducting sphere

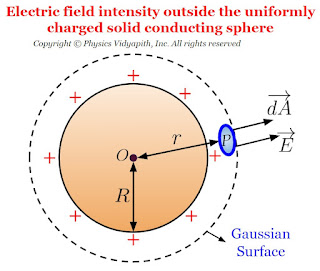

1.) Electric field intensity outside the solid conducting sphere:

If $O$ is the center of solid conducting spherical then the electric field intensity outside of the sphere can be determined by the following steps →

1.) First, take the point $P$ outside the sphere

2.) Draw a spherical surface of radius r which passes through point $P$. This hypothetical surface is known as the Gaussian surface.

3.) Now take a small area $\overrightarrow {dA} $ around point $P$ on the Gaussian surface to find the electric flux passing through it.

4.) Now find the direction between the electric field vector and a small area vector.

Due to uniform charge distribution, the electric field intensity will be the same at every point on the Gaussian surface. So from the figure,

The direction of electric field intensity on the Gaussian surface is radially outward which is in the direction of the area vector of the Gaussian surface. i.e. ($\theta=0^{\circ}$). Here $\overrightarrow {dA}$ is a small area around point $P$ so the small electric flux $d\phi_{E}$ will pass through this small area $\overrightarrow {dA}$. so this flux can be found by applying Gauss's law in question given below:

$ d\phi_{E}= \overrightarrow {E}\cdot \overrightarrow{dA}$

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA\: cos\: 0^{\circ} \quad \left \{\because \theta=0^{\circ} \right \}$

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA \quad (1) \quad \left \{\because cos\:0^{\circ}=1 \right \}$

The electric flux passes through the entire Gaussian surface, So integrate the equation $(1)$ →

$ \oint d\phi_{E}= \oint E\:dA $

$\phi_{E}=\oint E\:dA\qquad (2)$

According to Gauss's law:

$ \phi_{E}=\frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}\qquad (3)$

From equation $(2)$ and equation $(3)$, we can write as

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}=\oint E\:dA$

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}= E\oint dA$

Now substitute the area of the entire Gaussian spherical is $\oint {dA}=4\pi r^{2}$ in the above equation. So the above equation can be written as:

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}= E(4\pi r^{2})$

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r^{2}}$

From the above equation, we can conclude that the behavior of the electric field at the external point due to the uniformly charged solid conducting sphere is the same as the entire charge is placed at the center, point charge

If the surface charge density is $\sigma$, Then the total charge $q$ on the surface of a solid conducting sphere is→

$ q=4\pi R^{2}\: \sigma$

Substitute this value of charge $q$ in the above equation, so we can write the equation as:

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{4\pi R^{2}\: \sigma}{r^{2}}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_{0}}\frac{R^{2}}{r^{2}}$

This equation describes the electric field intensity at the external point of the solid conducting sphere.

2.) Electric field intensity on the surface of the solid conducting sphere:

If point $P$ is placed on the surface of the solid conducting sphere i.e. ($r=R$). so electric field intensity on the surface of the solid conducting sphere can be found by putting $r=R$ in the formula of electric field intensity at the external point of the solid conducting sphere:

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{R^{2}}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_{0}}$

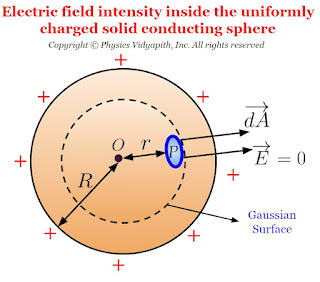

3.) Electric field intensity inside the solid conducting sphere:

If point $P$ is placed inside the solid conducting sphere then electric field intensity will be zero because the charge is distributed uniformly on the surface of the solid sphere and there will not be any charge on the Gaussian surface. So the electric flux will be zero inside the solid sphere. i.e.

$ \phi_{E}=\oint E\:dA$

$ 0=E\oint dA \qquad\quad \left \{ \because \phi_{E}=0 \right \}$

$ E=0$

Electric field intensity distribution with distance for Conducting Solid Sphere:

Electric field intensity distribution with distance shows that the electric field is maximum on the surface of the sphere and zero inside the sphere. Electric field intensity distribution outside the sphere reduces with the distance according to $E=\frac{1}{r^{2}}$.

B.) Electric field intensity at different points in the field due to the uniformly charged solid non-conducting sphere:

Let us consider, A solid non-conducting sphere of radius R in which $+q$ charge is distributed uniformly in the entire volume of the sphere. So electric field intensity at a different point due to the solid charged non-conducting sphere:

1.) Electric field intensity outside the solid non-conducting sphere:

Let us consider, An external point $P$ which is at a distance $r$ from the center point $O$ of the sphere. The electric flux is radially outward in the sphere. So the direction of the electric field vector and the small area vector will be in the same direction i.e. ($\theta =0^{\circ}$). Here $\overrightarrow {dA}$ is a small area, the small amount of electric flux will pass through this area i.e. →

$ d\phi_{E}= \overrightarrow {E}\cdot \overrightarrow{dA}$

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA\: cos\: 0^{\circ} \quad \left \{\because \theta=0^{\circ} \right \}$

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA \qquad (1) \quad \left \{\because cos\:0^{\circ}=1 \right \}$

The electric flux passes through the entire Gaussian surface, So integrate the equation $(1)$ →

$ \phi_{E}=\oint E\:dA\qquad (2)$

According to Gauss's law:

$ \phi_{E}=\frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}\qquad (3)$

From equation (1) and equation (2), we can write as

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}=\oint E\:dA$

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}= E\oint dA$

Now substitute the area of the entire Gaussian spherical surface is $\oint {dA}=4\pi r^{2}$ in the above equation. So the above equation can be written as:

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}= E(4\pi r^{2})$

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r^{2}}$

From the above equation, we can conclude that the behavior of the electric field at the external point due to the uniformly charged solid non-conducting sphere is the same as the point charge i.e. like the entire charge is placed at the center.

Since the sphere is a non-conductor so the charge is distributed in the entire volume of the sphere. So charge distribution can calculate by volume charge density →

$q=\frac{4}{3} \pi R^{3} \rho $

Substitute this value of charge $q$ in the above equation, so we can write the equation as:

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{4\pi R^{3}\: \rho}{3r^{2}}$

$ E=\frac{\rho}{\epsilon_{0}}\frac{R^{3}}{3r^{2}}$

This equation describes the electric field intensity at the external point of the solid non-conducting sphere.

2.) Electric field intensity on the surface of the solid non-conducting sphere:

If point $P$ is placed on the surface of a solid non-conducting sphere i.e. ($r=R$). so electric field intensity on the surface of a solid non-conducting sphere can be found by putting $r=R$ in the formula of electric field intensity at the external point of the solid non-conducting sphere:

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{R^{2}}$

$ E=\frac{\rho R}{3\epsilon_{0}}$

3.) Electric field intensity inside the solid non-conducting sphere:

If point $P$ is placed inside the sphere and the distance from the origin $O$ is $r$, the electric flux which is passing through the Gaussian surface

$ \phi_{E}= E.4\pi r^{2}$

Where $\phi_{E}=\frac{q'}{\epsilon_{0}}$

$ \frac{q'}{\epsilon_{0}}=E.4\pi r^{2}$

Where $q'$ is part of charge $q$ which is enclosed with Gaussian Surface

$ E=\frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q'}{r^{2}} \qquad \qquad (4)$

The charge is distributed uniformly in the entire volume of the sphere so volume charge density $\rho$ will be the same as the entire solid sphere i.e.

$ \rho=\frac{q}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R^{3}}=\frac{q'}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^{3}}$

$ \frac{q}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R^{3}}=\frac{q'}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^{3}}$

$ q'=q\frac{r^{3}}{R^{3}}$

$ q'=q\left (\frac{r}{R} \right)^{3}$

Put the value of $q'$ in equation $(4)$, so

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r^{2}}\left(\frac{r}{R} \right)^{3}$

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{qr}{R^{3}}$

Where $q=\frac{4}{3} \pi R^{3} \rho $. So above equation can be written as:

$ E=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}}\frac{\frac{4}{3} \pi R^{3} \rho r}{R^{3}}$

$E=\frac{ \rho r}{3 \epsilon_{0}}$

Electric field intensity distribution with distance for non-conducting Solid Sphere:

Electric field intensity distribution with distance shows that the electric field is maximum on the surface of the sphere and zero at the center of the sphere. Electric field intensity distribution outside the sphere reduces with the distance according to $E=\frac{1}{r^{2}}$.

2.) Electric field intensity on the surface of the solid conducting sphere

3.) Electric field intensity inside the solid conducting sphere

2.) Draw a spherical surface of radius r which passes through point $P$. This hypothetical surface is known as the Gaussian surface.

3.) Now take a small area $\overrightarrow {dA} $ around point $P$ on the Gaussian surface to find the electric flux passing through it.

4.) Now find the direction between the electric field vector and a small area vector.

- Electric field intensity outside the solid non-conducting sphere

- Electric field intensity on the surface of the solid non-conducting sphere

- Electric field intensity inside the non-solid conducting sphere

Derivation of Planck's Radiation Law

Derivation:

Let $ N$ be the total number of Planck’s oscillators and $E$ be their total energy, then the

average energy per Planck’s oscillator is

$ \overline{E}=\frac{E_{N}}{N}

\qquad (1)$

Let there be $ N_{0}, N_{1} ,N_{2}

,N_{3},---N_{n}$ oscillator having energy $ E_{0}, E_{1}, E_{2}, -- E_{n}$

respectively.

According to Maxwell’s distribution, the number of oscillators in the $ n^{th}$ energy

state is related to the number of oscillators in the ground state by

$ N_{n}=N _{0} e^{\tfrac{-nh\nu }{kt} }\qquad (2)$

Where

$ n$ is a positive integer. So put $ n= 1,2,3,…….$. The above equation can be

written for different energy states. i.e.

$ N_{1}=

N _{0} e^{\tfrac{-h\nu }{kt} }$

$ N_{2}=

N _{0} e^{\tfrac{-2h\nu }{kt} }$

$ N_{3}=

N _{0} e^{\tfrac{-3h\nu }{kt} }$

$.............$

$.............$

So, the total number of Planck’s Oscillators –

$ N= N _{0} +N_{1}+N_{2}+N_{3}+.... N_{n}$

Let $ x = e^{\frac{-h\nu }{kt}} \qquad (4) $

Then $ N = N_{0}[1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}+...+ x^{n}]$

$ N = \frac{N_{0}}{1-x} \qquad(5)$ [ from Binomial theorem]

Now the total energy of oscillators –

From equation $(4)$ put $ x = e^{\tfrac{-h\nu }{kt}}$ in above equation. i.e

$ E_{N } = N_{0}h\nu (x+2x^{2}+3x^{3}+...+nx^{n}) $

$ E_{N } = N_{0}h\nu x(1+2x+3x^{2}+....)$

$ E_{N } = \frac{N_{0}h\nu x}{(1-x)^{2}} \qquad(6)$ (from Bionomical theorem)

Now substituting the value of $N$ from equation $ (5)$ and $ E_{n}$ from equation

$ (6)$ in equation $ (1)$ –

$ \overline{E}= \frac{\frac{N_{0}h\nu x}{(1-x)^{2}}}{\frac{N_{0}}{(1-x)}}$

$ \overline{E}= \frac{h\nu }{(\frac{1}{x}-1)}$

$ \overline{E}= \frac{h\nu }{e^{\tfrac{h\nu }{kt}}-1} \qquad(7)$

The

number of oscillators per unit volume in wavelength range to $ ( \lambda + d\lambda )$ is $\frac{8\pi }{\lambda ^{4}} d\lambda$.

The energy per unit volume $ (E_{\lambda }d\lambda )$ in the wavelength range to $( \lambda

+d\lambda ) $ is –

$ E_{\lambda}d\lambda = \frac{8\pi }{\lambda ^{4}}d\lambda \overline{E} \qquad(8)$

From equation $ (7)$ and $ (8)$ –

$ E_{\lambda}d\lambda = \frac{8\pi }{\lambda ^{4}}d\lambda \frac{h\nu }{(e^{\tfrac{h\nu}{kt}}-1)}$

$ E_{\lambda}d\lambda = \frac{8\pi hc}{\lambda ^{5}} \frac{d\lambda}{(e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda kt}}-1)}$

The above equation describes Planck’s radiation law and this law was able to thoroughly explain the black body radiation spectrum.

Wien’s Displacement law from Planck’s Radiation Law:

Planck’s radiation law gives the energy in wavelength region $ \lambda to \lambda +d\lambda $ as –

$ E_{\lambda}d \lambda = \frac{8\pi hc}{\lambda ^{5}}(\frac{1}{e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda kt}}-1})d\lambda \qquad(1)$

For shorter wavelength $ \lambda T$ will be small and hence

$ e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda kt}}> > 1$

Hence, for a small value of $\lambda T$ Planck’s formula reduces to -

$ E_{\lambda}d \lambda = \frac{8\pi hc}{\lambda ^{5}}(\frac{1}{e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda kt}}})

d\lambda$

$ E_{\lambda}d\lambda = \frac{8\pi hc}{\lambda ^{5}}e^{\tfrac{-hc}{\lambda kt}}d\lambda$

$E_{\lambda}d\lambda = A \lambda ^{-5} e^{\tfrac{-hc}{\lambda kt}}d\lambda$

Where $ A = 8\pi hc$

The above equation is Wien’s law of energy distribution verified by Planck

radiation law.

Rayleigh-Jeans law from Planck’s Radiation Law:

According to Planck’s radiation law –

$ E_{\lambda}.d\lambda = \frac{8\pi hc}{\lambda ^{5}}\frac{1 }{e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda

kt}}-1}.d\lambda$

For longer wavelength $ e^{\frac{hc}{\lambda kt}}$ is small and can be expanded as-

$ e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda kt}} = 1+\frac{hc}{\lambda kt}+\frac{1}{2!}(\frac{hc}{\lambda kt})^{2}+....$

Neglecting the higher-order term –

$ e^{\tfrac{hc}{\lambda kt}} = 1+\frac{hc}{\lambda kt}$

Hence for longer wavelength, Planck’s formula reduces to –

$ E_{\lambda}.d\lambda = \frac{8\pi kt}{\lambda ^{5}}[\frac{1}{1+\frac{hc}{\lambda kt}-1}]$

$ E_{\lambda}.d\lambda = \frac{8\pi kt}{\lambda ^{4}}.d\lambda$

This is Rayleigh Jean’s law verified by Planck Radiation Law.

$ N= N _{0} + N_{0} e^{\tfrac{-h\nu }{kt}}+ N_{0} e^{\tfrac{-2h\nu

}{kt}}+...+ N_{0}e^{\tfrac{-nh\nu }{kt}}$

$ N= N _{0}[1+e^{\tfrac{-h\nu }{kt}}+e^{\tfrac{-2h\nu }{kt}}+.... e^{\tfrac{-nh\nu }{kt}}] \qquad(3)$

$ E_{N} = E_{0}N_{0}+ E_{1}N_{1}+ E_{2}N_{2}+...+ E_{n}N_{n}$

$ E_{N } = 0.N_{0}+ h\nu N_{0} e^{\tfrac{-h\nu }{kt}}+...+nh\nu N_{0} e^{\tfrac{-nh\nu }{kt}}$

$ E_{N } = N_{0}h\nu (e^{\tfrac{-h\nu }{kt}}+2e^{\tfrac{-2h\nu }{kt}}+...+ ne^{\tfrac{-nh\nu }{kt}})$

Orthogonality of the wave functions of a particle in one dimension box or infinite potential well

Description of Orthogonality of the wave functions of a particle in one dimension box or infinite potential well:

Let $\psi_{n}(x)$ and $\psi_{m}(x)$ be the normalized wave functions of a particle in the interval $(0, L)$ corresponding to the different energy level $E_{n}$ and $E_{m}$ respectively. These wave functions are:

$\psi_{n}(x)= \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} sin \frac{n \pi x}{L}$

$\psi_{m}(x)= \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} sin \frac{m \pi x}{L}$

Where $m$ and $n$ are integers.

In this function are real. Therefore

$\psi_{n}^{*}(x) = \psi_{n}(x)$

$\psi_{m}^{*}(x) = \psi_{m}(x)$

Where $m=n$,

$\int_{0}^{L} \psi_{n}^{*}(x) \psi_{m}^{*}(x) dx =0$

Hence, The function is mutually orthogonal in the interval $(0, L)$. These functions $\psi_{n}(x)$ and $\psi_{m}(x)$ are also normalized in this interval. The wave function, which is normalized and mutually orthogonal in an interval is said to form an orthogonal set in this interval. Since the wave function are zero outside the interval $(0, L)$, they are also orthogonal wave function in the whole range of $x$ axis in the interval $(-\infty, +\infty)$.

$\int_{0}^{L} \psi_{n}^{*}(x) \psi_{m}^{*}(x) dx = \frac{2}{L} \int_{0}^{L} sin \frac{m \pi x}{L} . sin \frac{n \pi x}{L} dx$

$\int_{0}^{L} \psi_{n}^{*}(x) \psi_{m}^{*}(x) dx =\frac{1}{L} \int_{0}^{L} \left[ cos \left\{ \frac{(m-n) \pi x}{L} \right\} - cos \left\{ \frac{(m+n) \pi x}{L} \right\} \right] dx $

$\int_{0}^{L} \psi_{n}^{*}(x) \psi_{m}^{*}(x) dx =\frac{1}{L} \left[ \frac{L}{\pi(m-n)} sin \left\{ \frac{(m-n) \pi x}{L} \right\} - \frac{L}{\pi(m+n)} sin \left\{ \frac{(m+n) \pi x}{L} \right\} \right]_{0}^{L} $

$\int_{0}^{L} \psi_{n}^{*}(x) \psi_{m}^{*}(x) dx =\frac{1}{L} \left[ \frac{L}{\pi(m-n)} sin \left\{ \frac{(m-n) \pi x}{L} \right\} - \frac{L}{\pi(m+n)} sin \left\{ \frac{(m+n) \pi x}{L} \right\} \right]_{0}^{L} $

The electric potential at different points (like on the axis, equatorial, and at any other point) of the electric dipole

Electric Potential due to an Electric Dipole:

The electric potential due to an electric dipole can be measured at different points:

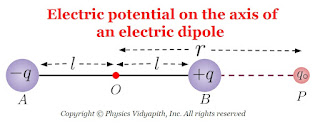

1. The electric potential on the axis of the electric dipole:

Let us consider, An electric dipole AB made up of two charges of -q and +q coulomb is placed in a vacuum or air at a very small distance of $2l$. Let a point $P$ is on the axis of an electric dipole and place at a distance $r$ from the center point $O$ of the electric dipole. Now put the test charged particle $q_{0}$ at point $P$ for the measurement of electric potential due to dipole's charges.

So Electric potential at point $P$ due $+q$ charge of electric dipole→

$ V_{+q}=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r-l}$

The electric potential at point $P$ due $-q$ charge of electric dipole→

$ V_{-q}=-\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r+l}$

Electric potential is a scalar quantity. Hence the resultant potential $V$ at the point $P$ will be the algebraic sum of the potential $V_{+q}$ and $V_{-q}$. i.e. →

$ V=V_{+q}+V_{-q}$

Now substitute the value of $V_{+q}$ and $V_{-q}$ in the above equation →

$ V= \frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r-l} -\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r+l}$

$ V= \frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{q}{r-l} - \frac{q}{r+l} \right]$

$ V= \frac{q}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{1}{r-l} - \frac{1}{r+l} \right]$

$ V= \frac{q}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{ \left( r+l \right)-\left (r-l \right)}{r^{2}-l^{2}} \right]$

$ V= \frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{2ql}{r^{2}-l^{2}} \right]$

$ V= \frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{p}{r^{2}-l^{2}} \right] \qquad \left( \because p=2ql\right)$

If $r$ is much larger then $2l$. So $l^{2}$ can be neglected in comparison to $r^{2}$. Therefore electric potential at the point $P$ due to the electric dipole is →

$ V= \frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{p}{r^{2}} \right] $

2. The electric potential on the equatorial line of the electric dipole:

Let us consider, An electric dipole AB made up of two charges of $+q$ and $-q$ coulomb are placed in vacuum or air at a very small distance of $2l$. Let a point $P$ be on the equatorial line of an electric dipole and place it at a distance $r$ from the center point $O$ of the electric dipole. Now put the test charged particle $q_{0}$ at point $P$ for the measurement of electric potential due to dipole's charges.

So Electric potential at point $P$ due $+q$ charge of electric dipole→

$ V_{+q}=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{BP}$

$ V_{+q}=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{\sqrt{r^{2}+l^{2}}}$

The electric potential at point $P$ due $-q$ charge of electric dipole→

$ V_{-q}=-\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{AP}$

$ V_{-q}=-\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{\sqrt{r^{2}+l^{2}}}$

$\therefore$ The resultant potential at point $P$ is

$ V=V_{+q}+V_{-q}$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{\sqrt{r^{2}+l^{2}}}-\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{\sqrt{r^{2}+l^{2}}} $

$V=0 $

Thus, the electric potential is zero on the equatorial line of a dipole (but the intensity is not zero). So No work is done in moving a charge along this line.

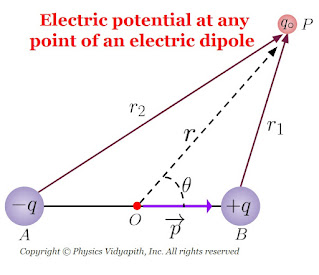

3. The electric potential at any point of the electric dipole:

Let us consider, an electric dipole $AB$ of length $2l$ consisting of the charge $+q$ and $-q$. Let's take a point $P$ in general and its distance is $r$ from the center point $O$ of the electric dipole AB.

Let the distance of point $P$ from the point $A$ and Point $B$ of the dipole is $PB=r_{1}$ and $PA=r_{2}$ respectively.

So, The electric potential at point $P$ due to the $+q$ charge of the electric dipole is →

$ V_{+q}=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r_{1}}$

$ V_{-q}=-\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r_{2}}$

The resultant potential at point $P$ is the algebraic sum of potential due to charges $+q$ and $-q$ of the dipole. That is

$ V=V_{+q}+V_{-q}$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r_{1}}-\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r_{2}}$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_{0}} \left(\frac{q}{r_{1}}-\frac{q}{r_{2}} \right) \qquad(1)$

$ r^{2}_{2}=r^{2}+l^{2}-2rlcos \left(\pi - \theta \right)$

$ r^{2}_{2}=r^{2}+l^{2}+2rlcos \theta \qquad(3)$

The equation $(2)$ may be expressed as →

$ r^{2}_{1}=r^{2} \left[1+ \frac{l^{2}}{r^{2}}-\frac{2l}{r}cos\theta \right] $

Taking distance $r$ much greater than the length of dipole (i.e. r>>l), so we may retain only first order term in $\frac{l}{r}$,

$ \therefore r^{2}_{1}=r^{2} \left[1- \frac{2l}{r}cos\theta \right]$

$ r_{1}=r \left[1- \frac{2l}{r}cos\theta \right]^{\frac{1}{2}}$

$ \frac {1}{r_{1}}=\frac{1}{r} \left[1- \frac{2l}{r}cos\theta \right]^{-\frac{1}{2}}$

Now applying the binomial theorem in the above equation. So we get

$ \frac {1}{r_{1}}=\frac{1}{r} \left[1+ \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right]$

Similarly,

$ \frac {1}{r_{2}}=\frac{1}{r} \left[1- \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right]$

Substituting these values in equation $(1)$, we get

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{q}{r} \left(1+ \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right)-\frac{q}{r} \left(1- \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right) \right]$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r} \left[ \left(1+ \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right)- \left(1- \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right) \right]$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r} \left[ \left(1+ \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right)- \left(1- \frac{l}{r}cos\theta \right) \right]$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r} \left[ \frac{2l cos\theta}{r}\right]$

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{2ql cos\theta}{r^{2}}\right]$

But $q\times 2l=p$ (dipole moment)

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{p cos\theta}{r^{2}}\right]$

The vector form of the above equation can be written as →

$ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}} \left[ \frac{\overrightarrow{p} \cdot \overrightarrow{r} }{r^{2}}\right]$

The above two equations hold only under the approximation that the distance of observation point $P$ is much greater than the size of the dipole.

Special Case:

Now comparing this result with the potential due to a point-charge, we see that:

- The electric potential on the axis of the electric dipole

- The electric potential on the equatorial line of the electric dipole

- The electric potential at any point of the electric dipole

Now simplify the above equation by applying the Geometry from the figure. i.e. From the figure, Acute angle $\angle POB$, we can write as,

$ r^{2}_{1}=r^{2}+l^{2}-2rlcos\theta \qquad(2)$

- At axial points $\theta=0^{\circ}$,

then $cos\theta= cos 0^{\circ}=1$,Therefore, $ V=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}} \frac{p}{r^{2}}$

- At equatorial points $\theta=90^{\circ}$,

then $cos\theta= cos 90^{\circ}=0$,Therefore,$ \quad V=0$

- In a fixed direction, that is , fixed $\theta$, $V\propto \frac{1}{r^{2}}$. here rather than $V \propto \frac{1}{r}$;

- Even for a fixed distance $r$, there is now a dependence on direction, that is, on $\theta$.

Electric field intensity due to uniformly charged plane sheet and parallel sheet

Electric field intensity due to a uniformly charged infinite plane thin sheet:

Let us consider, A plane charged sheet (It is a thin sheet so it will have

surface charge distribution whether it is a conducting or nonconducting

sheet) whose surface charge density is $\sigma$. From symmetry, Electric

field intensity is perpendicular to the plane everywhere and the field

intensity must have the same magnitude on both sides of the sheet. Let point

$P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$ be the two-point on the opposite side of the sheet.

To use Gaussian law, we construct a cylindrical Gaussian surface of

cross-section area $\overrightarrow{dA}$, which cuts the sheet, with points

$P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$. The electric field $\overrightarrow{E}$ is normal to

end faces and is away from the plane. Electric field $\overrightarrow{E}$ is

parallel to cross-section area $\overrightarrow{dA}$. Therefore the curved

cylindrical surface does not contribute to the flux i.e. $\oint

\overrightarrow{E} \cdot \overrightarrow{dA}=0$.Hence the total flux is

equal to the sum of the contribution from the two end faces. Thus, we get

$ \phi_{E}=\int_{A} \overrightarrow{E} \cdot

\overrightarrow{dA}+\int_{A} \overrightarrow{E} \cdot \overrightarrow{dA}$

$ \phi_{E}= \int_{A} E \: dA \:cos 0^{\circ} +\int_{A} E \: dA \:cos

0^{\circ} $

Here the direction of $\overrightarrow{E}$ and $\overrightarrow{dA}$ is same. So the angle will be $\theta = 0^{\circ}$.

$ \phi_{E}= \int_{A} E \: dA +\int_{A} E \: dA $

$ \phi_{E}= \int_{A} 2E \: dA $

$ \phi_{E}= 2E \int_{A} \: dA $

$ \phi_{E}= 2E\:A $

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}=2E\:A \qquad \left \{\because

\phi_{E}=\frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}} \right \}$

$ E=\frac{q}{2\epsilon_{0} A}$

$\because q=\sigma A $, So the above equation can be written as:

$ E=\frac{\sigma A}{2\epsilon_{0} A} $

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_{0}} $

Electric field intensity due to the uniformly charged infinite conducting

plane thick sheet or Plate:

Let us consider that a large positively charged plane sheet having a finite

thickness is placed in the vacuum or air. Since it is a conducting plate so the

charge will be distributed uniformly on the surface of the plate. Let

$\sigma$ be the surface charge density of the charge

Let's take a point $P$ close to the plate at which electric field intensity

has to determine. Since there is no charge inside the conducting plate, this

conducting plate can be assumed as equivalent to two plane sheets of charge

i.e sheet 1 and sheet 2.

The magnitude of the electric field intensity $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ at point $P$ due to sheet 1 is →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

The magnitude of the electric field intensity $\overrightarrow {E_{2}}$ at

point $P$ due to sheet 2 is →

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 2)

Since $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ and $\overrightarrow {E_{2}}$ are in the

same direction, the magnitude of resultant intensity $\overrightarrow {E}$

at point $P$ due to both the sheet is →

$ E=E_{1}+E_{2}$

$\because \quad E=\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_{0}}+\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_{0}}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_{0}} $

The resultant electric field will be away from the plate. If the plate is

negatively charged, the electric field intensity $\overrightarrow {E}$ would

be directed toward the plate.

We have obtained the above formula for a 'plane' charged conductor. In fact,

it holds for the electric field intensity 'just' outside a charged conductor

of any shape.

Electric field intensity due to two Infinite Parallel Charged Sheets:

When both sheets are positively charged:

Let us consider, Two infinite, plane, sheets of positive charge, 1 and 2 are

placed parallel to each other in the vacuum or air. Let $\sigma_{1}$ and

$\sigma_{2}$ be the surface charge densities of charge on sheet 1 and 2

respectively.

Let $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ and $\overrightarrow {E_{2}}$ be the electric

field intensities at any point due to sheet 1 and sheet 2 respectively.

Then,

The electric field intensity at points $P'$ →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 2)

Since, Electric field intensities $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ and

$\overrightarrow {E_{2}}$ are in the same direction, the magnitude of

resultant intensity at point $P'$ is given by →

$ E=E_{1}+E_{2}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2 \epsilon_{0}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2

\epsilon_{0}}$

$ E=\frac{1}{2 \epsilon_{0}} \left (\sigma_{1}+\sigma_{2} \right )$

If both sheets have equal charge densities $\sigma$ i.e.

$\sigma_{1}=\sigma_{2}=\sigma$, Then above equation can be written as:

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{ \epsilon_{0}} $

This electric field intensity would be away from both sheet 1 and sheet 2.

The electric field intensity at points $P$→

Electric field intensity at point $P$ due to sheet 1 is →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 2)

Now, both electric field intensities $\overrightarrow{E_{1}}$ and

$\overrightarrow{E_{2}}$ are in opposite direction. The magnitude of

resultant electric field $\overrightarrow{E}$ at point $P$ is given by

$ E= E_{1}-E_{2}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2 \epsilon_{0}}-\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2

\epsilon_{0}}$

$ E=\frac{1}{2 \epsilon_{0}} \left (\sigma_{1}-\sigma_{2} \right )$

If both sheets have equal charge densities $\sigma$ i.e.

$\sigma_{1}=\sigma_{2}=\sigma$, Then above equation can be written as:

$ E=0 $

The electric field intensity at points $P''$ →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away sheet 2)

Since, Electric field intensities $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ and

$\overrightarrow {E_{2}}$ are in the same direction, the magnitude of

resultant intensity at point $P''$ is given by →

$ E=E_{1}+E_{2}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2 \epsilon_{0}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2

\epsilon_{0}}$

$ E=\frac{1}{2 \epsilon_{0}} \left (\sigma_{1}+\sigma_{2} \right )$

If both sheets have equal charge densities $\sigma$ i.e.

$\sigma_{1}=\sigma_{2}=\sigma$, Then above equation can be written as:

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{ \epsilon_{0}} $

This electric field intensity would be away from both sheet 1 and sheet 2.

When one-sheet is positively charged and the other sheet negatively charged:

Let us consider two sheets 1 and 2 of positive and negative charge densities

$\sigma_{1}$ and $\sigma_{2}$ ($\sigma_{1} > \sigma_{2}$)

The electric field intensities at point $P'$ →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (toward from sheet 2)

The magnitude of the resultant electric field $E$

$ E=E_{1}-E_{2}$

$E= \frac{1}{2\epsilon_{0}} \left ( \sigma_{1}- \sigma_{2}\right )$

If both sheets have equal charge densities $\sigma$ i.e.

$\sigma_{1}=\sigma_{2}=\sigma$, Then above equation can be written as:

$ E=0 $

The electric field intensities at point $P$ →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (towards sheet 2)

Since, Electric field intensities $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ and

$\overrightarrow {E_{2}}$ are in the same direction, the magnitude of

resultant intensity at point $P$ is given by →

$ E=E_{1}+E_{2}$

$ E=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2 \epsilon_{0}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2

\epsilon_{0}}$

$ E=\frac{1}{2 \epsilon_{0}} \left (\sigma_{1}+\sigma_{2} \right )$

If both sheets have equal charge densities $\sigma$ i.e.

$\sigma_{1}=\sigma_{2}=\sigma$, Then above equation can be written as:

$ E=\frac{\sigma}{ \epsilon_{0}} $

The electric field intensities at point $P''$ →

$ E_{1}=\frac{\sigma_{1}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (away from sheet 1)

$ E_{2}=\frac{\sigma_{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}$ (toward from sheet 2)

The magnitude of the resultant electric field $E$ →

$ E=E_{1}-E_{2}$

$E= \frac{1}{2\epsilon_{0}} \left ( \sigma_{1}- \sigma_{2}\right )$

If both sheets have equal charge densities $\sigma$ i.e.

$\sigma_{1}=\sigma_{2}=\sigma$, Then above equation can be written as:

$ E=0 $

From the above expression, we can conclude that the magnitude of $E$ is free

from the 'position' of the point taken in the electric field between the

sheet and outside the sheet. It is also shown that the electric field

between the sheet is uniform everywhere and independent of separation

between the sheets.

|

| Infinite plane thin sheet |

$ \phi_{E}= \int_{A} E \: dA +\int_{A} E \: dA $

|

| Plane Charged Plate |

The magnitude of the electric field intensity $\overrightarrow {E_{1}}$ at point $P$ due to sheet 1 is →

|

| Likely positive charged sheet |

|

| Unlike charged parallel Sheet |

Electric field intensity due to uniformly charged wire of infinite length

Derivation of electric field intensity due to the uniformly charged wire of infinite length:

Let us consider a uniformly-charged (positively charged) wire of infinite length having a constant linear charge density (that is, a charge per unit length) $\lambda$ coulomb/meter. Let P is a point at a distance $r$ from the wire at which electric field $\overrightarrow{E}$ has to find.

Let us draw a coaxial Gaussian cylindrical surface of length $l$ through point $P$. By symmetry, the magnitude $E$ of the electric field will be the same at all points on this surface and directed radially outward.

Thus, Now take small area elements $dA_{1}$, $dA_{2}$ and $dA_{3}$ on the Gaussian surface as shown in figure below. Therefore, the total electric flux passing through area elements is:

$ \phi_{E}= \oint \overrightarrow{E} \cdot \overrightarrow{dA_{1}} + \oint \overrightarrow{E} \cdot \overrightarrow{dA_{2}} + \oint\overrightarrow{E} \cdot \overrightarrow{dA_{3}}$

$ \phi_{E}= \oint E\: dA_{1} cos\theta_{1} + \oint E\: dA_{2} cos\theta_{2} \\ \qquad + \oint E\: dA_{3} cos\theta_{3}$

The angle between the area element $dA_{1}$, $dA_{2}$ and $dA_{3}$ with electric field are $\theta_{1}= 0^{\circ}$ , $\theta_{2}= 90^{\circ}$, and $\theta_{3}=90^{\circ}$ respectively. So total electric flux

$ \phi_{E}= \oint E\: dA_{1} cos0^{\circ} + \oint E\: dA_{2} cos90^{\circ} \\ \qquad + \oint E\: dA_{3} cos90^{\circ}$

Here $cos \: 0^{\circ}=1$ and $cos \: 90^{\circ}=0$

Hence the above equation can be written as:

$ \phi_{E}= \oint E\:dA_{1} $

The total electric flux passing through the Gaussian surface is

$ \phi_{E}= \oint{E\:dA_{1}} $

$ \phi_{E}= E\:\oint{dA_{1}} $

$ \phi_{E}= E\:\left(2\pi r l \right) \qquad \left\{\because \oint{dA_{1}} =2\pi r l \right\} $

$ \phi_{E}= E\:\left(2\pi r l \right)$

But, By Gaussian's law, The total flux $\phi_{E}$ must be equal to $\frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}$, where $q$ is the total charge enclosed with the Gaussian surface. so that

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}= E\:\left(2\pi r l \right)$

$ E= \frac{q}{2\pi r l \epsilon_{0}}$

For linear charge distribution →

$q=\lambda l$

So substitute this value in the above equation which can be written as

$ E= \frac{\lambda l}{2\pi r l \epsilon_{0}}$

$ E= \frac{\lambda}{2\pi\epsilon_{0} r }$

The vector form of the above equation :

$\overrightarrow{E}= \frac{\lambda}{2\pi\epsilon_{0} r }\widehat{r}$

Where $\widehat{r}$ is a unit vector in the direction of $r$. The direction of $\overrightarrow{E}$ is radially outwards(for positively charged

wire).

Thus, the electric field ($E$) due to the linear charge is inversely proportional to the distance ($r$) from the linear charge and its direction

is outward perpendicular to the linear charge.

Special Note:

A charged cylindrical conductor behaves for external points as the whole charge is distributed along its axis.

Electric field intensity due to point charge by Gauss's Law

Derivation of electric field intensity due to a point charge by Gauss's Law:

Let us consider, a source point charge particle of $+q$ coulomb is placed at point $O$ in space. Let's take a point $P$ on the electric field of the source point charge particle. To find the electric field intensity $\overrightarrow{E}$ at point $P$, first put the test charge particle

$+q_{0}$ on the point $P$ and draw a gaussian surface which passes through the point $P$. After that take a very small area $\overrightarrow{dA}$ around the point $P$. If the distance between the source charge particle and small area $\overrightarrow {dA}$ is $r$ then electric flux passing through the small area $\overrightarrow{dA}$ →

$ d\phi_{E}= \overrightarrow{E} \cdot \overrightarrow{dA}$

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA\: cos\theta$

from the figure, the direction between $\overrightarrow{E}$ and $\overrightarrow{dA}$ is parallel to each other i.e. the angle will be $0^{\circ}$. So the above equation can be written as →

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA\: cos0^{\circ}$

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:dA $

The electric flux passing through the entire Gaussian surface and be found by closed integration of the above equation →

$ d\phi_{E}= \oint {E\:dA} $

$ d\phi_{E}= E\:\oint {dA} $

$ \phi_{E}= E\left(4\pi r^{2} \right) \qquad \left\{ \because \oint {dA}=4\pi r^{2} \right\}$

According to Gauss's Law → $\phi_{E}= \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}$ then above equation can be written as →

$ \frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}= E \left(4\pi r^{2} \right)$

$ E= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}} \frac{q}{r^{2}}$

The above expression is the electric field intensity due to a point source charged particle.

|

| Electric field due to point charge |

Normalization of the wave function of a particle in one dimension box or infinite potential well

Description of Normalization of the wave function of a particle in one dimension box or infinite potential well:

We know that the wave function for the motion of the particle along the x-axis is

$\psi_{n}(x)= A \: sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right) \quad \left\{ Region \quad 0 \lt x \lt a \right\}$

$\psi_{n}(x)= 0 \quad \left\{ Region \quad 0 \gt x \gt a \right\}$

The total probability that the particle is somewhere in the box must be unity. Therefore,

$\int_{0}^{L} \left| \psi_{n}(x)\right|^{2}dx =1$

Now substitute the value of the wave function in the above equation. Then

$\int_{0}^{L} \left| A \: sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right) \right|^{2}dx =1$

$\int_{0}^{L} A^{2} \: sin^{2} \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right) dx =1$

$ \frac{A^{2}}{2}\int_{0}^{L} \left[ 1- cos \left( \frac{2n \pi x}{L} \right) \right] dx =1$

$ \frac{A^{2}}{2} \left[ x - \left( \frac{L}{2n\pi} \right) sin \left( \frac{2n \pi x}{L} \right) \right]_{0}^{L} =1$

$ \frac{A^{2}}{2} \left[ L - \left( \frac{L}{2n\pi} \right) sin \left( \frac{2n \pi L}{L} \right) \right] =1$

$ \frac{A^{2}}{2} \left[ L - \left( \frac{L}{2n\pi} \right) sin \left( 2n \pi \right) \right] =1$

$ \frac{A^{2}}{2} \left[ L - \left( \frac{L}{2n\pi} \right) sin \left( 2n \pi \right) \right] =1$

$ \frac{A^{2}}{2} \left[ L - 0 \right] =1 \qquad(\because sin2n\pi =0)$

$ \frac{A^{2} L}{2} =1$

$ A= \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}$

Hence, the normalized wave function

$\psi_{n}(x)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)$

The absolute square $\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|^{2}$ of the wave function $\psi_{n}(x)$ gives the probability density. Hence

$\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|^{2} = \frac{2}{L} sin^{2} \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)$

The wave function for the particle in a box can be viewed in analogy with standing waves on a string. The wave function for a standing wave that has nodes at endpoints is of the form $\psi_{n}(x)= A \: sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)$. The condition for a standing wave can also be expressed in terms of wavelength.

$\lambda_{n}=\frac{2 \pi}{k_{n}}$

$\lambda_{n}=\frac{2 \pi}{\frac{n \pi}{L}} \qquad \left( \because k_{n}=\frac{n \pi}{L} \right)$

$\lambda_{n}=\frac{2 L}{n}$

$L= \frac{n \: \lambda_{n}}{2}$

So,

$L= \frac{\: \lambda_{1}}{2} \qquad \left( for \: n=1 \right)$

$L= \lambda_{2} \qquad \left( for \: n=2 \right)$

$L= \frac{3 \: \lambda_{3}}{2} \qquad \left( for \: n=3 \right)$

$L= 2 \lambda_{4} \qquad \left( for \: n=4 \right)$

Geo structure of wave function $\psi_{n}(x)$ and wave function's density $\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|^{2}$.

Variation of the wave function and probability of finding the particle in a one-dimensional box:

We know that normalised wave function $\psi_{n}(x)$

$\psi_{n}(x)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)$

The probability density of wave function $\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|$

$\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|^{2} = \frac{2}{L} sin^{2} \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)$

Maximum Condition:

The values of $\psi_{n}(x)$ and $\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|^{2}$ will be maximum. When

$sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)=1$

$sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right )=sin \frac{\left( 2m+1 \right) \pi}{2}$

$ \frac{n \pi x}{L} =\left( 2m+1 \right) \frac{ \pi}{2}$

$ x =\left( 2m+1 \right) \frac{ L}{2n}$

Minima Condition:

The values of $\psi_{n}(x)$ and $\left| \psi_{n}(x) \right|^{2}$ will be minima. When

$sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)=0$

$sin \left( \frac{n \pi x}{L} \right)= \sin \: m\pi$

$ \frac{n \pi x}{L} = \: m\pi$

$x=m\left( \frac{L}{n} \right)$

The electric potential energy of an electric dipole in the uniform electric field

Derivation of the electric potential energy of an electric dipole in the uniform electric field:

Let us consider an electric dipole $AB$, which is made up of two charges $q_1$ and $q_2$, which are placed at a distance of $2l$ in the electric field $E$. So force acting on each charge due to the electric field will be $qE$. If the dipole gets rotated a small-angle $d\theta$ against the torque acting on it in the uniform electric field $E$ then the small work done is

$dW=\tau. d\theta \qquad (1)$

The torque (i.e moment of force) on an electric dipole in a uniform electric field

$ \tau=p.E\:sin\theta$

Now substitute the value of $\tau$ in equation $(1)$. So work done

$ dW=p.E\:sin\theta.d\theta$

If the dipole rotate the angle from $\theta_{1}$ to angle $\theta_{2}$ then workdone

$\int_{W_{1}}^{W_{2}}dW=p.E\int_{\theta_{1}}^{\theta_{2}}sin\theta \: d\theta$

$ W_{2}-W_{1}=p.E\left[-cos\theta \right]_{\theta_{1}}^{\theta_{2}}$

$ \Delta W= p.E \left( cos\theta_{1}-cos\theta_{2} \right)\qquad\qquad (2)$

This work is stored in the form of the electric potential energy of an electric dipole in the electric field. So

$U=\Delta W$

$U=p.E \left( cos\theta_{1}-cos\theta_{2} \right)$

If the electric dipole rotates from $0^{\circ}$ (when the direction of electric dipole moment $p$ is aligned in the direction of the electric field $E$) to an angle $\theta$ in the electric field i.e $\theta_{1}=0^{\circ}$ and $\theta_{2}=\theta$ then the electric potential energy of dipole in a uniform electric field

$U=p.E (1-cos\theta)$

Case-(I) If $\theta=0^{\circ}$ i.e It is stable equilibrium position then

$U_{min}=0$

Case-(II) If $\theta=90^{\circ}$ i.e Position of zero energy then

$U=pE$

Case-(III) If $\theta=180^{\circ}$ i.e It is unstable equilibrium position then

$U_{max}=2pE$

|

| Force of moment on an electric Dipole |

de-Broglie Concept of Matter wave

Louis de-Broglie thought that similar to the dual nature of light, material particles must also possess the dual character of particle and wave. This means that material particles sometimes behave as particle nature and sometimes behave like a wave nature.

According to de-Broglie –

According to Planck’s theory of radiation–

$E=h\nu \qquad(1) $

Where

h – Planck’s constant

$\nu $ - frequency

According to Einstein’s mass-energy relation –

$E=mc^ {2} \qquad (2)$

According to de Broglie's hypothesis equation $ (1)$ and equation $(2)$ can be written as –

$mc^ {2} = h \nu$

$mc^ {2} = \frac{hc}{\lambda }$

$\lambda =\frac{h}{mc}\qquad(3) $

$\lambda =\frac{h}{P}$

Where $P$ –Momentum of Photon

Similarly from equation $(3)$ the expression for matter waves can be written as

Here $P$ is the momentum of the moving particle.

1.) de-Broglie Wavelength in terms of Kinetic Energy

$K=\frac{1}{2} mv ^{2}$

$K=\frac{m^{2}v^{2}}{2m}$

$K=\frac{P^{2}}{2m}$

$P=\sqrt{2mK}$

Now substitute the value of $P$ in equation $ (4)$ so

2.) de-Broglie Wavelength for a Charged particle

The kinetic energy of a charged particle is $K = qv$

Now substitute the value of $K$ in equation$(5)$ so

3.) de-Broglie Wavelength for an Electron

The kinetic energy of an electron

$K=ev$

If the relativistic variation of mass with a velocity of the electron is ignored then $m=m_{0}$ wavelength

So wavelength of de-Broglie wave associated with the electron in non-relativistic cases

4.) de-Broglie wavelength for a particle in Thermal Equilibrium

For a particle of mass $m$ in thermal equilibrium at temperature $T@

$K=\frac{3}{2}kT$

Where $K$ – Boltzmann Constant

$\lambda =\frac{h}{\sqrt{2m.\frac{3}{2}kt}}$

Properties of matter wave →

A moving particle is always associated with a wave, called as de-Broglie matter-wave, whose wavelengths depend upon the mass of the particle and its velocity.

h – Planck’s constant

$\nu $ - frequency

| $\lambda=\frac{h}{mv}=\frac{h}{P}\qquad(4)$ |

| $\lambda =\frac{h}{\sqrt{2mK}} \qquad (5)$ |

| $\lambda =\frac{h}{\sqrt{2mqv}}$ |

| $\lambda =\frac{h}{\sqrt{2m_{0}ev}}$ |

| $\lambda =\frac{h}{\sqrt{3mKT}}$ |

- Matter waves are generated only if the material's particles are in motion.

- Matter-wave is produced whether the particles are charged or uncharged.

- The velocity of the matter wave is constant; it depends on the velocity of material particles.

- For the velocity of a given particle, the wavelength of matter waves will be shorter for a particle of large mass and vice-versa.

- The matter waves are not electromagnetic waves.

- The speed of matter waves is greater than the speed of light.

According to Einstein’s mass-energy relation$E=mc^{2}$$h\nu = mc^{2}$$\nu =\frac{mc^{2}}{h}$Where $\nu$ is the frequency of matter-wave.We know that the velocity of matter-wave$ u =\nu \lambda $

Substitute the value of $\nu$ in the above equation$u =\frac{mc^{2}}{h}. \lambda $

$u =\frac{mc^{2}}{h} . \frac{h}{mv}$$u =\frac{c^{2}}{v}$ Where $v$ → particle velocity which is less than the velocity of light. - The wave and particle nature of moving bodies can never be observed simultaneously.

Group velocity is equal to particle velocity

Prove that: Group velocity is equal to Particle Velocity

Solution:

We know that group velocity

$V_{g}=\frac{d\omega}{dk}$

$V_{g}=\frac{d(2\pi\nu )}{d(\frac{2\pi }{\lambda })} \qquad \left(k=\frac{2\pi}{\lambda} \right)$

$V_{g}=\frac{d\nu}{d(\frac{1}{\lambda })}$

$\frac{1}{V_{g}}=\frac{d( \frac{1}{\lambda })}{d\nu}\qquad(1)$

We know that the total energy of the particle is equal to the sum of kinetic energy and potential energy. i.e

$E=K+V$

Where

$K$ – kinetic energy

$V$ – Potential energy

$E=\frac{1}{2} mv^{2}+V$

$E-V=\frac{1}{2}\frac{(mv)^2}{m}$

$E-V=\frac{1}{2m }(mv)^2$

$2m(E-V)=(mv)^2$

$mv=\sqrt{2m(E-V)}$

According to de-Broglie wavelength-

$\lambda =\frac{h}{mv}$

$\lambda =\frac{h}{\sqrt{2m(E-V)}}$

$\frac{1}{\lambda} =\frac{\sqrt{2m(E-V)}}{h}\qquad(3)$

Now put the value of $\frac{1}{\lambda }$ in equation$(1)$

$\frac{1}{V_{g}} =\frac{d}{dv}[\frac{{2m(E-V)}^\tfrac{1}{2}}{h}]$

$\frac{1}{V_{g}} =\frac{d}{dv}[\frac{{2m(h\nu -V)}^\tfrac{1}{2}}{h}]$

$\frac{1}{V_{g}} =\frac{1}{2h}[{2m(h\nu -V)}]^{\tfrac{-1}{2}}{2m.h}$

$\frac{1}{V_{g}} =\frac{1}{2h}[{2m(E -V)}]^{\tfrac{-1}{2}}{2m.h} \qquad \left(\because E=h\nu \right) $

$\frac{1}{V_{g}} =\frac{m}{mv}$ {from equation $(2)$}

$V_{g}=V$

Thus, the above equation shows that group velocity is equal to particle velocity.

$V$ – Potential energy

Principle, Construction and Working of Venturimeter

Principle of Venturimeter:

It is a device for measuring the rate of liquid flow through pipes. Its principle and workings are based on Bernoulli's theorem and equation.

Construction:

It consists of two identical coaxial tubes, $X$ and $Z$, connected by a narrow coaxial tube $Y$. Two vertical tubes $P$ and $Q$ are mounted on tubes $X$ and $Y$ to measure the pressure of the liquid that flows through pipes. As shown in the figure below.

Working and Theory:

Connect this venturimeter horizontally to the pipe through which the liquid is flowing and note down the difference of liquid columns in tubes $P$ and $E$. Let the difference be $h$.

Let us consider that an incompressible and non-viscous liquid flows in streamlined motion through a tube $X$,$Y$, and $Z$ of a non-uniform cross-section.

Now Consider:

The cross-section's area of tube $X$ = $A_{1}$

The cross-section's area of tube $Y$ = $A_{2}$

The velocity of fluid per second (i.e., equal to distance) at the cross-section of tube $X$ = $v_{1}$

The velocity of fluid per second (i.e., equal to distance) at the cross-section of tube $Y$ = $v_{2}$

The fluid's pressure at cross-section of tube $X$ = $P_{1}$

The fluid's pressure at cross-section of tube $Y$ = $P_{2}$

Now the change in pressure on tube $P$ and $Q$:

$P_{1}-P_{2}=\rho g h \qquad(1)$

Where $\rho$ is the density of the liquid.

According to the principle of continuity:

$A_{1} v_{1} = A_{2} v_{2} = \frac{m}{\rho}= V \quad(2)$

Where $V$ is the volume of the liquid flowing per second through the pipe. Then from equation $(2)$

$\left.\begin{matrix}

v_{1}=\frac{V}{A_{1}}

\\

v_{2}=\frac{V}{A_{2}}

\end{matrix}\right\} \qquad(3)$

Now apply Bernoulli's Theorem for horizontal flow (i.e, $h_{1}=h_{2}$) in a verturimeter.

$P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_{1}^{2} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_{2}^{2} $

$P_{1} - P_{2} = \frac{1}{2}\rho v_{2}^{2} - \frac{1}{2} \rho v_{1}^{2} $

$P_{1} - P_{2} = \frac{1}{2}\rho \left( v_{2}^{2} - v_{1}^{2} \right) \qquad(4) $

Now from equation $(1)$ and equation $(4)$, we get

$\rho g h = \frac{1}{2}\rho \left( v_{2}^{2} - v_{1}^{2} \right)$

$g h = \frac{1}{2} \left( v_{2}^{2} - v_{1}^{2} \right)$

Now substitute the value of $v_{1}$ and $v_{2}$ from equation $(3)$ in above equation

$g h = \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{V^{2}}{A^{2}_{2}} - \frac{V^{2}}{A^{2}_{1}} \right)$

$g h = \frac{V^{2}}{2} \left( \frac{1}{A^{2}_{2}} - \frac{1}{A^{2}_{1}} \right)$

$g h = \frac{V^{2}}{2} \left( \frac{ A^{2}_{1} - A^{2}_{2} }{A^{2}_{1} A^{2}_{2}} \right)$

$V^{2} = \frac{2 g h A^{2}_{1} A^{2}_{2}}{A^{2}_{1} - A^{2}_{2}}$

$V = A_{1} A_{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 g h }{A^{2}_{1} - A^{2}_{2}}}$

Hence flow rate of liquid can be calculated by measuring $h$, since $A_{1}$ and $A_{2}$ are known for the given venturimeter.

|

The cross-section's area of tube $Y$ = $A_{2}$

The velocity of fluid per second (i.e., equal to distance) at the cross-section of tube $X$ = $v_{1}$

The velocity of fluid per second (i.e., equal to distance) at the cross-section of tube $Y$ = $v_{2}$

The fluid's pressure at cross-section of tube $X$ = $P_{1}$

The fluid's pressure at cross-section of tube $Y$ = $P_{2}$

Solution of electromagnetic wave equations in conducting media

The electromagnetic wave equations in conducting media:

For electric field vector:

$ \nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{E}-\mu \epsilon\frac{\partial^{2} \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t^{2}} - \sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}=0 \qquad(1)$

For magnetic field vector:

$\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{B} - \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial^{2} B}{\partial t^{2}}-\sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t}=0 \qquad(2)$

The wave equation of electric field vector:

$\overrightarrow{E}(\overrightarrow{r},t)=E_{\circ} e^{i(\overrightarrow{k}. \overrightarrow{r} - \omega t)} \qquad(3)$

The wave equation of magnetic field vector:

$\overrightarrow{B}(\overrightarrow{r},t)=B_{\circ} e^{i(\overrightarrow{k}. \overrightarrow{r} - \omega t)} \qquad(4)$

Now the solution of electromagnetic wave for electric field vector.

Differentiate with respect to $t$ of equation $(3)$

$\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}=i \omega E_{\circ} e^{i(\overrightarrow{k}. \overrightarrow{r} - \omega t)}$

Again differentiate with respect to $t$ of the above equation:

$\frac{\partial^{2} \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t^{2}}=i^{2} \omega^{2} E_{\circ} e^{i(\overrightarrow{k}. \overrightarrow{r} - \omega t)}$

$\frac{\partial^{2} \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial^{2} t}=- \omega^{2} \overrightarrow{E}(\overrightarrow{r},t)$

Now substitute the value of the above equation in equation$(1)$

$\nabla^{2} \overrightarrow{E}=-\omega^{2} \mu \epsilon \overrightarrow{E} - i \omega \mu \sigma \overrightarrow{E}$

$\nabla^{2} \overrightarrow{E}=- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right) \overrightarrow{E}$

This is the solution of the electromagnetic wave equation in conducting media for the electric field vector.

Now component form of the above equation:

$(\frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial x^{2}} + \frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial y^{2}} +\frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial z^{2}})(\hat{i}E_{x}+\hat{j}E_{y}+\hat{k}E_{z}) \\ =- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right)(\hat{i}E_{x}+\hat{j}E_{y}+\hat{k}E_{z}) \qquad(5)$

If the wave is propagating along $z$ direction. Then for uniform-plane electromagnetic waves-

$\frac{\partial}{\partial x}=\frac{\partial}{\partial y}=0$

$\frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial x^{2}}=\frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial y^{2}}=0$

$E_{z}=0$

Now the equation $(5)$ can be written as:

$\frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial x^{2}} (\hat{i}E_{x}+\hat{j}E_{y}) \\ =- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right)(\hat{i}E_{x}+\hat{j}E_{y})$

Now separate the above equation in $x$ and $y$ components so

$\left.\begin{matrix}

\frac{\partial^{2} E_{x}}{\partial z^{2}}=- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right) E_{x}

\\

\frac{\partial^{2}E_{y}}{\partial z^{2}} =- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right) E_{y}

\end{matrix}\right\} \quad(6)$

The solution of electromagnetic wave for magnetic field vector can find out by following the above method.

Therefore $x$ and $y$ components of the solution of the electromagnetic wave equation for magnetic field vector can be written as. i.e.

$\left.\begin{matrix}

\frac{\partial^{2} B_{x}}{\partial z^{2}}=- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right) B_{x}

\\

\frac{\partial^{2}B_{y}}{\partial z^{2}} =- \left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right) B_{y}

\end{matrix}\right\} \quad(7)$

In the solution of electromagnetic wave equation $(6)$ and equation $(7)$. The term $\left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right)$ is equal to $k_{z}^{2}$. It is known as propagation constant $k_{z}$. Then

$k_{z}^{2}=\left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right) \qquad(8)$

The propagation constant is the complex quantity so

$k_{z}=\alpha+i \beta \qquad(9)$

Now from equation $(8)$ and equation $(9)$

$\left(\alpha+i \beta \right)^{2}=\left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right)$

$\alpha^{2} - \beta^{2} +2 i \alpha \beta =\left( \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon + i \omega \mu \sigma \right)$

Now separate the real and imaginary terms:

$Real \: Term \rightarrow \alpha^{2} - \beta^{2} = \omega^{2} \mu \epsilon \quad (10)$

$Imaginary \: Term \rightarrow 2 \alpha \beta = \omega \mu \sigma \quad (11)$

On solving the equation $(10)$ and equation $(11)$

$\alpha= \omega \sqrt{\frac{\mu \epsilon}{2}} \left[ 1 + \left\{ 1+ \left( \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon \omega} \right)^{2} \right\}^{1/2} \right]^{1/2} \quad(12)$

$\beta= \omega \sqrt{\frac{\mu \epsilon}{2}} \left[ \left\{ 1+ \left( \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon \omega} \right)^{2} \right\}^{1/2} -1 \right]^{1/2} \quad(13)$

The wave equation $(3)$ of the electric field vector also can be written as:

$\overrightarrow{E}(\overrightarrow{r},t)=E_{\circ} e^{-\beta \overrightarrow{r}}e^i{(\alpha \overrightarrow{r} - \omega t)} \qquad(14)$

The above equation has an additional term $e^{-\beta \overrightarrow{r}}$ compared to the purely harmonic solution.

Where

$\alpha \rightarrow$ Attenuation Constant

$\beta \rightarrow$ Absorption Coefficient and Phase Constant

$\alpha \rightarrow$ Attenuation Constant

$\beta \rightarrow$ Absorption Coefficient and Phase Constant

Electromagnetic Wave Equation in Conducting Media (i.e. Lossy dielectric or Partially Conducting)

Maxwell's Equations:

Maxwell's equation of the electromagnetic wave is a collection of four equations i.e. Gauss's law of electrostatic, Gauss's law of magnetism, Faraday's law of electromotive force, and Ampere's Circuital law. Maxwell converted the integral form of these equations into the differential form of the equations. The differential form of these equations is known as Maxwell's equations.

For Conducting Media:

Current density $(\overrightarrow{J}) = \sigma \overrightarrow{E} $

Volume charge distribution $(\rho)=0$

Permittivity of Conducting Media= $\epsilon$

Permeability of Conducting Media=$\mu$

Now, Maxwell's equation for Conducting Media:

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{E}=0 \qquad(1)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{B}=0 \qquad(2)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E}=-\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} \qquad(3)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{H}= \overrightarrow{J}$

Modified form for Conducting Media:

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}= \mu \overrightarrow{J}+\mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}= \mu \sigma \overrightarrow{E}+ \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} \qquad(4)$

Now, On solving Maxwell's equation for conducting media i.e perfect dielectric and lossless media, gives the electromagnetic wave equation for conducting media. The electromagnetic wave equation has both an electric field vector and a magnetic field vector. So Maxwell's equation for conducting medium gives two equations for electromagnetic waves i.e. one is for electric field vector($\overrightarrow{E}$) and the second is for magnetic field vector ($\overrightarrow{H}$).

Electromagnetic wave equation for conducting media in terms of $\overrightarrow{E}$:

Now from equation $(3)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E}=-\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} $

Now take the curl on both sides of the above equation$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times (\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E})=-\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} $

We know that

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{E}=0 $

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}.\overrightarrow{\nabla}=\nabla^{2}$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}=\sigma \mu \overrightarrow{E} + \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} $

Now substitute these values in equation $(5)$. So

$ -\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{E}=-\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \left(\sigma \mu \overrightarrow{E} + \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} \right)$

$ -\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{E}=-\mu \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \left(\sigma \overrightarrow{E} + \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} \right)$

$ \nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{E}=\mu \epsilon \frac{\partial^{2} \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t^{2}} + \sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} $

$ \nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{E}-\mu \epsilon \frac{\partial^{2} \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t^{2}} - \sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}=0 $

The value of $\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu \epsilon}}= v$. Where $v$ is the speed of the electromagnetic wave in the conducting medium. So the above equation is often written as

$ \nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{E}-\frac{1}{v^{2}}\frac{\partial^{2} \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t^{2}} - \sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}=0 $

This is an electromagnetic wave equation for conducting media in terms of electric field vector ($\overrightarrow{E}$).

Electromagnetic wave equation for conducting media in terms of $\overrightarrow{B}$:

Now from MAxwell's equation $(4)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}= \mu \sigma \overrightarrow{E}+ \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}$

Now take the curl on both sides of the above equation

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times (\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B})=\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \left( \mu \sigma \overrightarrow{E}+ \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} \right) $

$(\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{B}).\overrightarrow{\nabla} - (\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{\nabla}).\overrightarrow{B} \\ =\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \sigma \mu \overrightarrow{E}+ \mu \epsilon \left( \overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} \right)$

$(\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{B}).\overrightarrow{\nabla} - (\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{\nabla}).\overrightarrow{B} \\ =\sigma \mu \left( \overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E} \right)+ \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left( \overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E} \right) \qquad(6)$

We know that

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{B}=0$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}.\overrightarrow{\nabla}=\nabla^{2}$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E}= -\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t}$

Now substitute these values in equation $(6)$. So

$-\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{B}=- \sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} - \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial^{2} B}{\partial t^{2}}$

$\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{B}= \sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} + \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial^{2} B}{\partial t^{2}} $

$\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{B}-\sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} - \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial^{2} B}{\partial t^{2}}=0 $

The value of $\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu \epsilon}}= v$. Where $v$ is the speed of the electromagnetic wave in the conducting medium. So the above equation is often written as

$\nabla^{2}.\overrightarrow{B} - \frac{1}{v^{2}} \frac{\partial^{2} B}{\partial t^{2}}-\sigma \mu \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t}=0 $

This is an electromagnetic wave equation for conducting media in terms of electric field vector ($\overrightarrow{B}$).

- $\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{E}= \frac{\rho}{\epsilon_{0}}$

- $\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{B}=0$

- $\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E}=-\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t}$

- $\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}= \mu \overrightarrow{J}$

Modified form:$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}= \mu \overrightarrow{J}+\mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t}$

Volume charge distribution $(\rho)=0$

Permittivity of Conducting Media= $\epsilon$

Permeability of Conducting Media=$\mu$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{B}=0 \qquad(2)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E}=-\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t} \qquad(3)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{H}= \overrightarrow{J}$

$(\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{E}).\overrightarrow{\nabla} - (\overrightarrow{\nabla}. \overrightarrow{\nabla}).\overrightarrow{E}=-\frac{\partial}{\partial t} (\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}) \qquad(5)$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}.\overrightarrow{\nabla}=\nabla^{2}$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{B}=\sigma \mu \overrightarrow{E} + \mu \epsilon \frac{\partial \overrightarrow{E}}{\partial t} $

$\overrightarrow{\nabla}.\overrightarrow{\nabla}=\nabla^{2}$

$\overrightarrow{\nabla} \times \overrightarrow{E}= -\frac{\partial \overrightarrow{B}}{\partial t}$

Popular Posts

-

Let $S$ be a point monochromatic source of light of wavelength $\lambda$ placed at the focus of collimating lens $L_{1}$. The light beam is ...

-

Angle of Acceptance → "If incident angle of light on the core for which the incident angle on the core-cladding interface equals t...

-

Derivation of interference of light due to a wedge-shaped thin film: Interference of light due to wedge-shaped thin film The wedge...

-

Maxwell's Equations: Maxwell's equation of the electromagnetic wave is a collection of four equations i.e. Gauss's law of elec...

-

Let a plane wavefront be incident normally on slit $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$ of equal $e$ and separated by an opaque distance $d$.The diffracted l...

Study-Material

Categories

Alternating Current Circuits

(10)

Atomic and Molecular Physics

(4)

Biomedical

(1)

Capacitors

(6)

Classical Mechanics

(12)

Current carrying loop in magnetic field

(5)

Current Electricity

(10)

Dielectric Materials

(1)

Electromagnetic Induction

(3)

Electromagnetic Wave Theory

(23)

Electrostatic

(22)

Energy Science and Engineering

(2)

Error and Measurement

(2)

Gravitation

(11)

Heat and Thermodynamics

(3)

Kinematics Theory Of Gases

(2)

Laser System & Application

(15)

Magnetic Effect of Current

(9)

Magnetic Substances

(3)

Mechanical Properties of Fluids

(5)

Nanoscience & Nanotechnology

(4)

Nuclear Physics

(7)

Numerical Problems and Solutions

(2)

Optical Fibre

(5)

Optics

(25)

Photoelectric Effect

(3)

Quantum Mechanics

(37)

Relativity

(8)

Semiconductors

(2)

Superconductors

(1)

Topic wise MCQ

(9)

Units and Dimensions

(1)

Waves

(5)