What is Transformation Equation?

Galilean Transformation Equation:

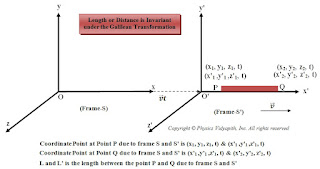

Let us consider, two frames $S$ and $S'$ in which frame $S'$ is moving with constant velocity $v$ relative to an inertial frame $S$. Let

$ \overrightarrow{r'}=\overrightarrow{r}-\overrightarrow{v}t\qquad (1)$

In component form, the coordinate are related by the equations

$\overrightarrow{x'}=\overrightarrow{x}-\overrightarrow{v}t;\quad y'=y; \quad z'=z\qquad (2)$

The equation $(1)$ and equation $(2)$ express the transformation of coordinates from one inertial frame to another. Hence they are referred to as Galilean transformation.

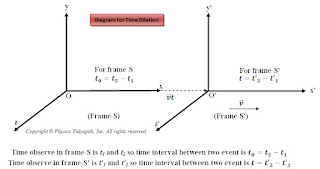

The equation $(1)$ and equation $(2)$ depending on the relative motion of two frames of reference, but it also depends upon certain assumptions regarding the nature of time and space. It is assumed that the time t is independent of any particular frame of reference. i.e. If $t$ and $t'$ be the times recorded by observers $O$ and $O'$ of an event occurring at $P$ then

$ t=t'\qquad (3)$

Now add the above assumption with transformation equation $(3)$ so the Galilean transformation equations are

$ \begin{Bmatrix} x'=x-vt\\ y'=y\\ z'=z\\ t'=t \end{Bmatrix}\qquad (4)$

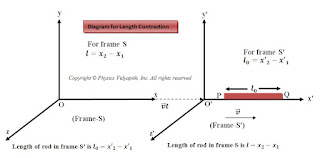

The other assumption, regarding the nature of space, is that the distance between two points (or two particles) is independent of any particular frame of reference. For example if a rod has length $L$ in the frame $S$ with the end coordinates $(x_{1}, y_{1}, z_{1})$ and $(x_{2}, y_{2}, z_{2})$ then

$L=\sqrt{(x_{2}-x_{1})^{2}+(y_{2}-y_{1})^{2}+(z_{2}-z_{1})^{2}}\quad (5)$

At the same time, the end coordinate of the rod in frame $S'$ are $(x'_{1}, y'_{1}, z'_{1})$ and $(x'_{2}, y'_{2}, z'_{2})$ then

$ L'=\sqrt{(x'_{2}-x'_{1})^{2}+(y'_{2}-y'_{1})^{2}+(z'_{2}-z'_{1})^{2}}\qquad (6)$

But for any time $t$ from equation $(4)$

$ \begin{Bmatrix} x'_{2}-x'_{1}=x_{2}-x_{1}\\ y'_{2}-y'_{1}=y_{2}-y_{1}\\ z'_{2}-z'_{1}=z_{2}-z_{1} \end{Bmatrix}\quad\quad\quad (7)$

$L=L'$

Thus, the length or distance between two points is invariant under Galilean Transformation.

The hypothesis of Galilean Invariance:(Principle of Relativity)

The hypothesis of Galilean invariance is based on experimental observation and is stated as follows:

OR in other words

Modify the hypothesis of Galilean Invariance by giving the following statement-

Failure of Galilean Relativity OR Galilean Transformation:

There are the following points that could not explain by Galilean transformation:

A point or a particle at any instant, in space has different cartesian coordinates in the different reference systems. The equation which provide the relationship between the cartesian coordinates of two reference system are called Transformation equations.

- The origin of the two frames coincide at $t=0$

- The coordinate axes of frame $S'$ are parallel to that of the frame $S$ as shown in the figure below

- The velocity of the frame $S'$ relative to the frame $S$ is $v$ along x-axis;

So from equation $(5)$, equation $(6)$ and equation $(7)$, we can write as:

The basic laws of physics are identical in all reference system which move with uniform velocity with respect to one another.

The basics laws of physics are invariant in inertial frame.

The basic law of physics are invariant in form in two reference system which are connected by Galilean Transformation

- Galilean Transformation failed to explain the actual result of the Michelson-Morley experiment.

- It violates the postulates of the Special theory of relativity.

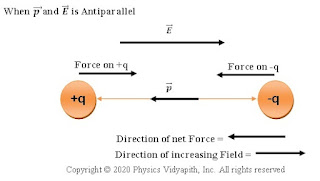

According to Maxwell's electromagnetic theory, the speed of light in a vacuum is $c$ $(3\times10^{8} m/sec)$ in all directions. Let us consider a frame of reference relative to which the speed of light is $c$ in all directions, According to Galilean transformation the speed of light in any other inertial system, which is in relative motion with respect to the former, will be different in a different direction. For example- If an observer is moving with speed $v$ opposite or along with the propagation of light, The speed of light $c_{0}$ in the frame of the observer is given by

$ c_{0}=c\:\pm \: v$